Oak trees’ northernly planetary distribution coincides with the largest land masses and populations of human beings. It is no wonder that Oak trees have fascinated humanity since ancient times. Oaks have been prized for their bounty: food, medicine, and materials. In the regions where they grow large, the image of the tree and its leaves evoke a myriad of emotions. Their importance in culture is reflected by the services which oak trees provide to the environment in the wild. In the modern arboretum (pl. arboreta), a living museum of trees and shrubs, the fascinating world of oaks and their shared history with humanity is revealed.

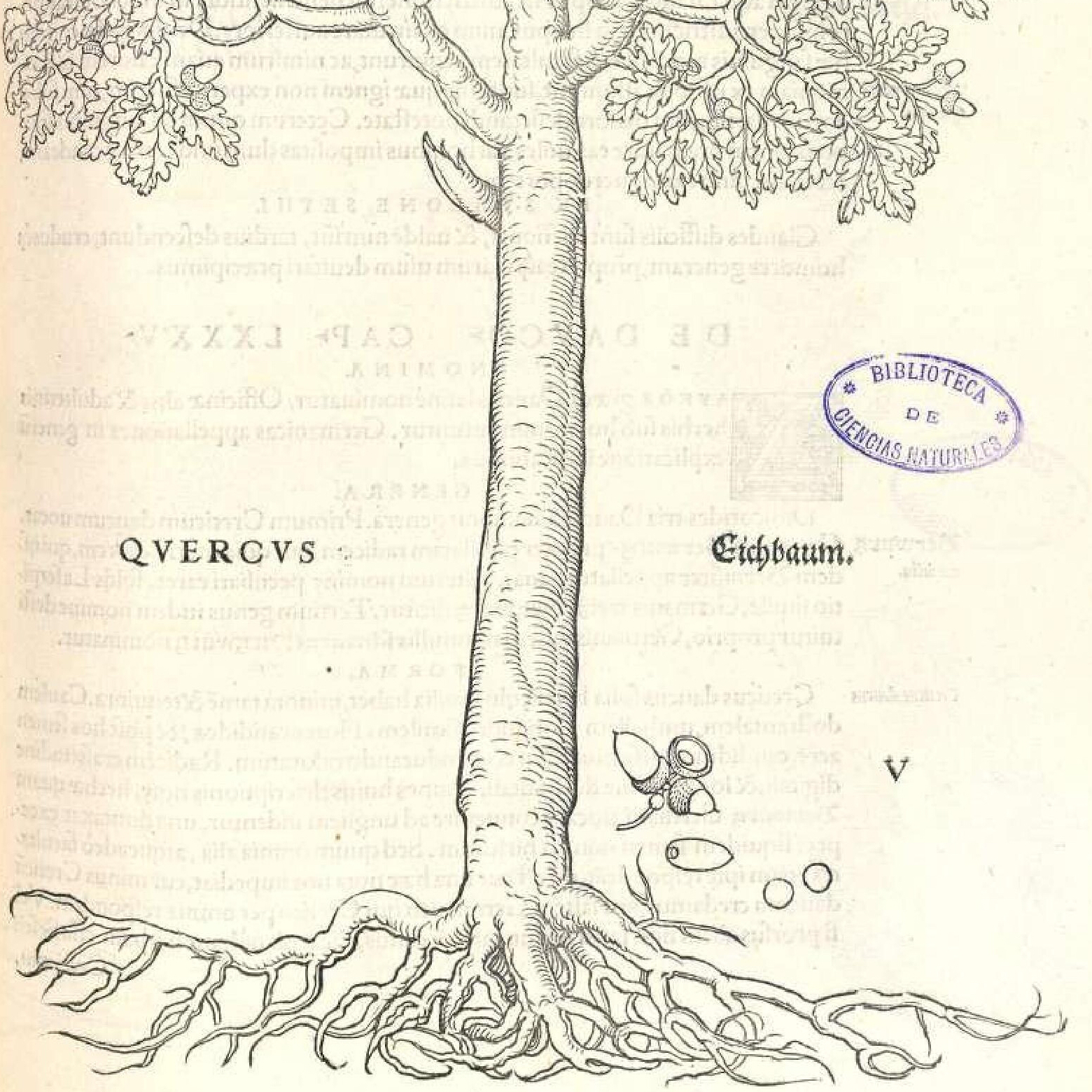

Oak trees, in the mind of Carolus Linnaeus and modern botanists, are said to make up the genus Quercus. There are many species of oaks, some of which are easy to identify and others which are extremely hard to tell apart. Some oak species are notorious for high rates of interspecific hybridization, which require further analysis. The shape of the acorn fruit has separated oaks more consistently than any of its other notorious characteristics. In the midwestern United States of America, oak leaves take a myriad of forms but sometimes have simple ovular forms that are more common nearer to the equator and reaching its southern range in Colombia. The Andean Oak, Quercus humboldtii, characterizes the versatility of the genus, Quercus.

Roble, the Spanish name for Oak, holds a dear place in the industrious culture of the Spanish oak forests that provide the diet of swine, a source of cork, and shade across this peninsula approaching Africa. After the establishment of Spanish populations across the Americas, Roble developed into the term used to distinguish familiar trees in the southern hemisphere. These austral trees are far different in their natural history from oak trees, they hold such a strong connection to their northernly counterparts that their Genus bears the name Nothofagus, the southern antithesis to the family of trees Fagaceae and related to the genus Fagus, or Beech trees, another tree of Europe.

Our cultural connection to the Oak tree is a factor in the introduction of oaks into the urban environment, and in some cases artificially increasing their abundance in the landscape. However, their popularity can create the conditions for pathogens to develop and spread from clone to clone, or species to species. Their diversity in the wilderness has become an asset to the ongoing breeding of resistant oak street trees. Oaks have replaced Elms in many regions where the previously popular street tree was apparently ravaged by disease.

Intercontinental hybridization, a byproduct of humanity’s recent maritime capacity, provided an opportunity to produce unique characteristics to respond to the environmental stresses related to climate shifts and disease. Time will tell if this process is a viable alternative. One of the many criticisms is that the intercontinental hybridization of oaks can alter pre-existing ecosystems. Many of these questions delve into ethical dilemmas regarding the role of human intervention in nature and its consequences, and can create polarizing arguments. On one hand, even natural events such as volcanic events could drastically impact our climate and could necessitate human intervention to create a landscape with a semblance of what it used to be. Man made or influenced events could also necessitate adaptation. On the other hand, our perception of these risks may not be proportionate to the time scale to which they would occur, and our rapid response of breeding and species introduction could prove to have consequences of its own. These issues are at the foundation of arboreta and the reason why it’s so important to study trees in controlled environment prior to implementing radical change.

In comparison to other arboreta, the UW-Madison Arboretum is unique in its history since it functions largely as a nature preserve and fosters research surrounding issues involving the restoration of natural habitats. Of the many areas within the UW-Arboretum, the Longenecker Horticultural Gardens (LHG) reflects best the traditional style of arboreta, which is a garden of trees and shrubs designed for study but also a place for leisure and relaxation. This study can involve testing their adaptability to the environment, a place to grow and showcase new varieties, and cultural center where art and nature can coexist to the tastes of its audience and curator.

These photos were taken on Nov 13th, 2017. It happened to be a very warm fall, which contributed to the fact that many of the leaves still were on the trees. Some didn’t even change color! Enjoy.

Latin and English equivalents

Quercus x warei – Regal Oak hybrid

Quercus robur – English Oak

Quercus petraea – Durmast Oak

Quercus macdanielii – Heritage Oak

Quercus ilicifolia – Scrub Oak

Quercus bimondorum – Prairie Stature Oak

Quercus coccinea – Scarlet Oak

Quercus bicolor – American Dream Swamp White Oak

bibdigital.rjb.csic.es/idviewer/13865/256

Further reading

Evelyn, John. 1706. Sylva. Vol 1. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/20778/20778-h/20778-h.htm